This is going to be a rant: so if you don’t care about obscure early 20th-century fantasy writers in general, or E. R. Eddison in particular, look away now.

I have a long-standing love affair with Eddison’s works. (And not just the fantasy, either: his translation of Egils Saga is hot stuff.) I first came across his books when I was about eighteen. At that point, I was sufficiently inexperienced a reader that I didn’t quite what to make of them. I knew that their language was beautiful, if rich, obtuse and difficult to handle; that the man could tell a story of a kind that I had never seen before; and that this was going to be one of those looooong relationships. I had that part of the evaluation right, anyway.

I still have some of the Eddison books that I bought in that first flush of infatuation. The copy of Mistress of Mistresses has had its cover reinforced with the kind of textured see-through “ConTact” plastic that people use on bathroom windows. The other two volumes of the Ballantine paperback editions of the Zimiamvian Trilogy seem not to have been given the plastic treatment, and as a result are incredibly beat up. When I realized that I couldn’t find my first paperback copy of The Worm Ouroboros, as a stopgap — never call it a replacement — I went to Abebooks and ordered a hardcover copy of one of the American editions. That’s one book that I can’t be without. In one of its characters, Eddison has defined a character trait of mine that I couldn’t have described until I read it in his pages — and it would be Lord Gro, that quintessentially ambivalent and thoughtful traitor, with whom I share it. Eddison describes Gro as one who “ever perversely affecteth the losing side in a quarrel.”

While the Worm is a straightforward — well, not straightforward; incredibly complex and lush — swashbuckling fantasy, the Zimiamvian books are something else. (And here I have to congratulate my speech transcription software, which having been corrected only once, now knows how to spell “Zimiamvian”. Dragon NaturallySpeaking rules.) In these three books — Mistress of Mistresses, A Fish Dinner in Memison, and the incomplete The Mezentian Gate — Eddison has set up an extraordinary set of universes between which certain lucky human beings pass to and fro, not always knowing how or why. And gods — or rather the Goddess for whom all creation was made (and not the one you’re thinking of, either: this is no sweet-tempered, PC Gaia, though Graves would have recognized Her) and Her Consort — do the same, passing literally from lifestyle to lifestyle, between times, between dimensions, from mortality to immortality and back again, sometimes in the blink of an eye. It’s all for fun (for Them, anyway); it’s all in deadly earnest; and it’s all otherwise indescribable. These fantasy novels are like no others written before or since (so Tolkien said: and maybe he would know). I’m not going to get into too much other detail about the books here: others have done a far better job of analyzing or critiquing Eddison’s work than I could. See here, and here, for example.

The books’ print history was spotty. They had hardcover editions in the thirties and forties, but I think all of them were largely lost until the Ballantine fantasy paperback series brought them back into print in the sixties. That’s the vintage of my original paperbacks. Since then I’ve slowly been able to score some of the earlier hardcover editions: the most recent of these is a first US edition of Mistress of Mistresses, with all Keith Henderson’s graphic “decorations” intact. But since their original publication in hardcover, the books have never had the kind of popular attention that other fantasy novels have acquired. (It’s worth noting at this point that when Fellowship of the Ring first came out, many of its reviewers compared it favorably to Eddison’s work, which at that point had been out for some years.)

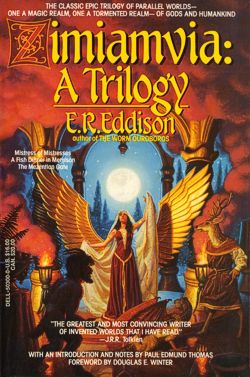

So I got very interested when I discovered that, in 1992, Dell Books had published an omnibus edition of the Zimiamvian books: Zimiamvia, A Trilogy, featuring extensive annotations by Paul Edmund Thomas, who had gone to the Bodleian and the library in Leeds where Eddison’s papers are kept to do his research. I promptly took myself off to Abebooks again and ordered a used copy.

It’s one of those doorstop trade paperbacks, as you might imagine: nine hundred and eighty-five pages. I was delighted to get my hands on it. I didn’t even mind that the cover was one that doesn’t really work, somehow managing to look both very earnest and very dim at the same time. There’s Fiorinda standing in the middle of the scene, holding up a length of starry chiffon veiling and gazing off into some weird upper middle distance (sort of behind and above your left shoulder) as if she’s trying to figure out where the drapes should go. (sigh) Oh well: bad covers happen. I should know.

But then you get to the insides of the book. There’s a foreword and a long introduction, and then the three books themselves. The text is footnoted all over the place. Oh, good, I thought. At the end, you get more than a hundred pages of footnotes, plus appendices containing a chronology, a list of dramatis personae, genealogical tables, and maps. And possibly best of all, interspersed with the material which appeared as the (poshumously) published version of the incomplete The Mezentian Gate, you get unpublished notes, outlining and other material — all (to me anyway) a lot more interesting than what Peter scornfully refers to as “Tolkien’s Book of Lost Laundry Lists, Volume 8“.

So there it is. Obviously a huge work of scholarship: months of time and research. Yummy. I dug in…

…and was really saddened to discover how flawed the scholarship is.

Let me pause to say how very right Edwards gets it when he does get it right. There’s a ton of information here about Eddison, his life, his work, and his thought, that can’t easily be found anywhere else. I would buy Edwards dinner any time I ever met him to thank him for everything that worked.

But oh, the stuff that doesn’t!!

I bought this book primarily as a way to find out more about three books I already knew well and loved. My chief interest, therefore, was in the notes. Imagine my annoyance, then, to find out that many of them are…well…just wrong.

And I don’t mean about subjective matters. I mean about things like translations of proverbs or poetry which you can look up easily in many common sources online and off. Eddison’s work is thoroughly peppered with quotes in all kinds of languages: Attic Greek, Latin, French, German, you name it. Getting the translations right, especially with an eye to illuminating how the quotes affect the story, would seem to be something of an imperative. For example: The Latin proverb “Bis dat quae tarde” means “She gives twice who gives slowly”, not “She who gives slowly gives in two ways.” …Okay, that seems minor: but some of these translations really look like Edwards didn’t ask anybody — like he just pulled out a Latin dictionary and hoped for the best.

Not a hanging offense, perhaps. (I told you this was a rant.) But there are places where a wrong translation can really matter. In one scene, the Vicar of Rerek (one of the bad-guy characters, but one whom Eddison loved so much that it’s hard not to love him too…) has a dream about two other characters (the primary protagonist, a man named Lessingham, and the woman/goddess Lessingham loves). In the dream, the Vicar sees the words UT COMPRESSA PEREAT, and everyone in the dream reacts with shock/horror. My Latin, when I saw the words first, was rocky enough that I didn’t trust my own translation: so one day, when I happened to think about the issue, I called up C. J. Cherryh — who besides being one of the most talented SF writers I know, has also been a Latin teacher. Carolyn didn’t even have to stop to think. “It means ‘She whom you embraced is destroyed,’ or ‘is perished,'” Carolyn said. Perfect: bearing in mind what’s going to happen to poor Queen Antiope shortly, that absolutely makes sense. (And interestingly, this is exactly the same translation that an online Latin dictionary gave me about a month ago, when this issue first came up.) …But where did Edwards get the vague, weird translation that appears in his footnote? “Let that pressed, constrained, dissembling woman perish…” He was in Oxford: there must have been somebody he could ask!

And this kind of thing keeps happening. Because he had someone to help him with the Old French quotations, he seems to have gotten them right. But where he didn’t seek help, the meaning (in various languages) suffers again and again. This is no service to a new reader. Heck, I knew what was going on in the books in most cases, and the notes started to confuse me. I started looking at note after note and wondering, “is this right…? Or just kind of right?”

This is not a good thing for a work of scholarship to be making you think. And then it got worse, because I started to run into the jokes in the footnotes. All innocently I was reading a note on Scylla and Charybdis —

“A rival lover and wife of Poseidon, the nereid Amphitrite, with magic herbs turned Scylla into a six-headed monster. Supposedly, Scylla never failed to catch six sailors, one with each head, from every passing ship. Such errorless fielding in the modern age would make even Kent Hrbek doff his cap.”

Ooooookay. Well, I thought, after nine hundred pages of inserting footnotes, the annotator’s entitled to a joke. On we go.

And then I ran into this one.

“‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’: The poem is named for its central character, the wild-eyed, sirenlike faerie woman of hypnotic and fatal beauty, who lures men, unsuspecting and alone in their cars, when she hitchhikes by the roadside. The English translation of the French title is, of course, ‘The Beautiful Woman Without a Mercedes.'”

Ooooookay. Well, he’s allowed two, right? …And then, a few pages further on, in a note on the legend of Melusine:

“In anger at her father, Melusine imprisons him in a mountain, yet her mother does not appreciate the vengeful act; she casts a spell that turns Melusine into a serpent from the waist down every Saturday. Pressina places a condition on her daughter’s reptilian transformation: if Melusine can find a hiusband who’ll agree to stay away from her on Saturdays, she will be released from her snaky punishment. Melusine marries Count Raymond of Lusignan and tells him that she can never spend Saturdays with him because she has joined a ladies’ golf league that plays thirty-six holes every Saturday. Raymond, who like Sean Connery, proudly maintains a low handicap…” (What, have we fallen into the notes for a P. G. Wodehouse novel all of a sudden??) “…and who, also like Sean Connery, detests playing golf with women, cheerfully agrees to leave her alone for half of every weekend. The happy couple have several children, but each one is born with some monstrous birth defect. One of Raymond’s brothers suspiciously whispers to him that the children are deformed because they have been fathered by some lover that Melusine sees every Saturday. Raymond suspects her caddy, and enraged, he storms into her room, where he sees her in her serpent form. She immediately leaves, and he never sees her again. Supposedly after her death, she haunts the castle grounds, and many have testified to hearing her mournful voice weeping for her children. But the more acute listeners hear her calling ‘Fore!’ and weeping for a shot that she topped into the pond near the seventh green.”

Uhhh… okay. I think the annotator needs a time-out.

But no. Two pages later, correcting what may be an error in chemistry in one of the Goddess’s bits of dialogue: “Aqua regia, which receives its kingly name from its ability to dissolve the noble metals, is a combination not of aqua fortis (nitric acid) and vitriol (sulphuric acid), but of aqua fortis and muriatic (hydrochloric) acid. As the song goes, ‘Don’t know much about chemistry: that’s because I’m Aphrodite.”

…(sigh) Look, of course jokes get stuck into serious work (and the not-so-serious). I’ve done it myself. But you take them out before you go to press. Hitting this stuff again and again leaves the reader wondering what to believe…an unfortunate effect in a work of scholarship.

It’s still a great book. And if I run into Edwards at some convention, I’m going to buy him that dinner…because he really has done tremendous work here. But I’m not going to let him leave the restaurant until I find out what happened with those footnotes. Sheesh!

…End of rant. Time for an omelet aux herbes and another argument with some wizards of my acquaintance.

[tags]Eddison, E.R. Eddison, Zimiamvia, Fiorinda, Barganax, Lord Gro, British fantasy, A Fish Dinner in Memison, Mistress of Mistresses, The Mezentian Gate[/tags]