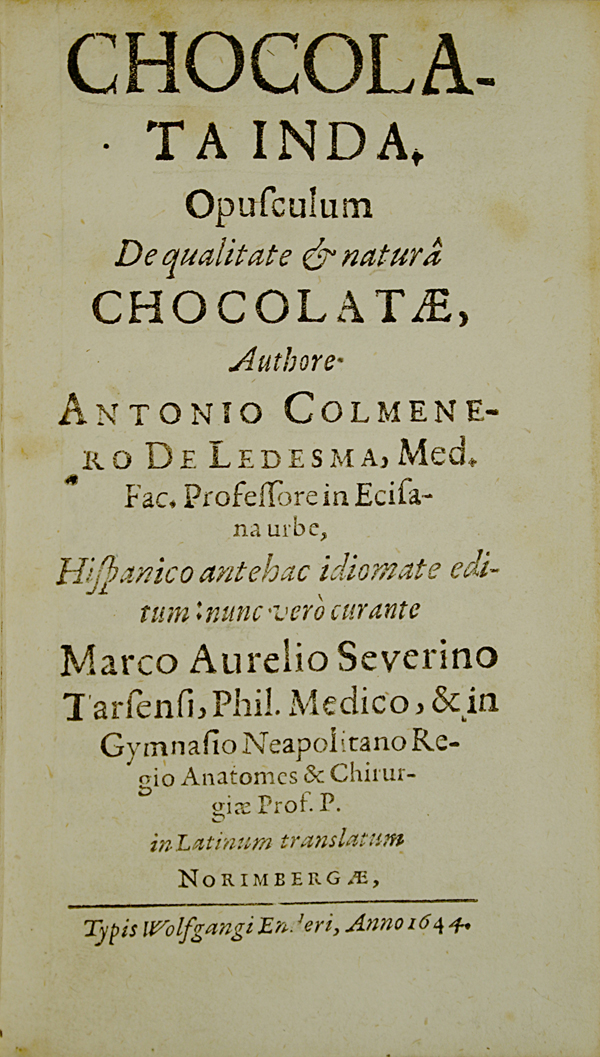

The second I saw it, the image above turned into a kind of mental “money shot” for me. I’d been awaiting this particular movie with interest for a long time, but not until I saw this image from The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey did the hair stand up on the back of my neck and the little voice whisper in my ear, “Start marking off days on the calendar.” Yesterday The Big Day finally came, and I went up to Dublin to see the film in the best possible company. What follows are some very broad and non-spoiler-y notes on the experience.

Just so you know what previous affiliations may color this review: I first read Tolkien’s work in my mid-teens, loved it instantly, and have returned to it repeatedly, for pleasure and sometimes comfort, all my adult life. So am I a fan? Yes. (So was my seatmate at the film, my collaborator / spouse Peter Morwood, though he came at Middle-Earth from the opposite direction: The Hobbit first, then the Lord of the Rings trilogy.) That said, I think I can set aside fondness and fandom for long enough to review what I’ve seen with a relatively clear eye.

Having seen the original LotR film trilogy and loved it—with only the most minor niggles about creative choices—I was still a bit concerned; for in terms of adaptation, it seemed to me that The Hobbit was always going to be a hard road to walk in terms of getting the tone right. The Hobbit is extremely different from the Lord of the Rings books, plainly intended (as we too-coyly put it these days) “for younger readers”. It was always going to be a challenging work to bring to the screen when a lot of the prospective audience would be adults who’d seen the LotR film trilogy, and were used to something in a more starkly grown-up mode. I was a bit nervous that, with creative imperatives simultaneously dragging it in such different directions, the movie might not work.

Well, I needn’t have worried. That leads to my initial answer to the question: should you go see this film? Yes. Will you be satisfied with this film if you’re a Tolkien fan of the I-read-the-books-now-convince-me-you-haven’t-ruined-them school? I think so.

Let me set aside a couple of meta- or marginal issues first: first of all, the fact that Jackson chose to shoot the film in the higher-definition 48 frames-per-second format, untried until now in a major release. I didn’t find myself bothered by it in the least. Peter and I saw the film in its 3D version, and found the 48fps format not at all distracting or strange—in fact, I’m not sure I would have noticed it if I hadn’t been prewarned. Everything just seemed very clear. And the 3D seemed well-handled and not overdone. Obviously your mileage may vary: but I mention this because it’s been a big issue for some people.

Also: in regard to those reviewers who’re wandering around muttering “I don’t know how you can get three movies out of this one small book…” Sorry, but I don’t have much patience with this attitude. It seems to come chiefly from those who haven’t done their homework, ignoring the interviews with Jackson that clearly detail how the film’s writers went back to the Appendices attached to the LotR books for extensive backstory / background material. These reviewers’ position strikes me as similar to one that might be taken by someone who—having seen, for example, a series of Le Carre-based “cold war”-period films—then tries to claim that you couldn’t possibly get three big films out of the whole of World War II. The Appendices at the end of The Return of the King sketch out, in the briefest detail, centuries of uneasy history between the time when Sauron was first dispatched and the time when he becomes a serious problem in LotR: centuries in which the dark power that once rose in Mordor begins its slow and stealthy reconsolidation further afield. I looked over Tolkien’s bare-bones timeline last night, to make sure my memory of it was correct, and with my screenwriter hat on I could easily see three movies implicit in one page of that material. (I’m half tempted to do a Nothing-But-Spoilers review leading into a tentative breakdown, with an eye to what we’ve seen in the first film, of what the structures of the next two films could be like. Another time maybe.) It’s a pity that some reviewers can’t take the time to inform their opinions before trotting them out the door, but such is life. From where I sit, the advice is: Ignore them and go enjoy the show.

“Incineration…?!” …Martin Freeman and Refusing The Call as

an art form

…So back to the film at hand. About the acting there’s not much to say except that it’s always at the very least workmanlike, and sometimes terrific. When you have a big ensemble cast, with so much going on, getting all the introductions made is always going to be problematic: a lot of us can’t even name all the Seven Dwarves, after all these years, and suddenly here we are with twelve… Suffice it to say, this crowd of characters gets handled as well as it might be. Richard Armitage stands out in the crowd, but he in particular has a hard row to hoe; he has to carry the weight of the character work that will turn Thorin Oakenshield into a hero worth following, without leaving you thinking of him as nothing more but a sort of height-challenged bargain-basement Aragorn. The problem is increased by Thorin’s (canonical) distrust of Bilbo, which has to be established strongly enough to register as a problem, yet not so much so as to make him unsympathetic. (And for me this was a close one: I do remember myself thinking, “If this doesn’t get sorted out pretty soon, he’s going to come off as a real dick.” But it gets sorted, as it must.)

Martin Freeman, standing at the core of the story, does as Bilbo Baggins what he usually does, seemingly effortlessly: he makes the part his own until you find it hard to imagine anyone else in it. He starts out (apparently) a little hesitantly, but it’s my opinion that this was both an acting choice and a directorial one. To make Bilbo too proactive too soon would be a misstep, as he’s standing in for all of us in regard to how we’d behave if the house suddenly filled up with dwarves, and how most people would handle the ensuing physical and emotional turmoil that Thorin’s business proposition will provoke.

You’ll hear complaints from some quarters about these early sequences being painted in too-broad strokes, or overplayed for comic effect. But where it counts, the real business is if anything underplayed. In particular, in the crucial moments when the adventurous and much-suppressed Took side of Bilbo’s emotional heredity starts slipping out of the shadows and asserting itself, the temptation to go for any Meaningful Close-up has been wisely resisted. We get nothing but a medium angle, and kind of a remote one at that, of Bilbo sitting leaned up against a wall and listening, just listening with all of him to what’s going on in his sitting room. The way his body’s held, and the still hunger in the character’s face, between them say everything that needs to be said about Bilbo’s secret longing for adventure… and remind us that Martin Freeman can do more with his face while holding it still than many actors can while twisting theirs around every which way. (One word here, also, to my fellow Sherlock fans: toward the end of the film there’s a spot—no, two—where I think you will see, on Freeman’s face, a kind of shadow or presentment of an expression we’ll sooner or later see Dr. John Watson turn on his long-missing partner in the Work. In its present context, though, the expressions and the acting go straight to the core of the character’s interior business, in a flash completely changing the way you see him.)

At any rate, in short order Bilbo gets himself together and things get going. I for one didn’t begrudge the leisurely induction: it’s like the slow climb of the roller coaster up to the first big drop. And like a rollercoaster ride, everything after that starts to happen very fast indeed. Sometimes almost too fast: I could have occasionally wished for a touch more breathing space between sequences… but that’s personal preference. Soon enough we get to the point where Bilbo is walking into Rivendell, and what had originally seemed simply hectically real starts (for me at least) to acquire additional depth.

“Now it is a strange thing,” Tolkien says in The Hobbit, “but things that are good to have and days that are good to spend are soon told about, and not much to listen to: while things that are uncomfortable, palpitating, and even gruesome, may make a good tale, and take a deal of telling anyway.” Tolkien gives Thorin’s company a couple of weeks in Rivendell, and it would have made me happier (from the fix-this-problem-in-the-typewriter side of the brain) if even just a few more days there had been implied in the theatrical release. This would have put right a whiff of the (canonically) too-coincidental that occurs here, and also would have allowed time to set up a signpost to Bilbo’s personal sense of wonder, longing, and the depth of his regret at leaving. A few shots of montage would be all it would have taken to deepen and fully establish this sense, so that later when (at a bad moment) Bilbo says that he wants to go back to Rivendell, it doesn’t sound quite so much as if he’s simply chickening out. (Out of context, I’ve seen some images that suggest this material may well appear in the Extended Edition that’s almost certain to come out on DVD in the fullness of time.)

In terms of other character business that might possibly have been augmented a bit—there is muttering from some quarters also about Gandalf being a little too wizard-ex-machina in this film. I can only shrug and say that the beats are canonical, and too much foreshadowing of Gandalf’s assets and abilities here strikes me as counterproductive: the dwarves are plainly as much in the dark about exactly what he can do as Bilbo is. One thing I do like in this: we get to see Gandalf be a bit of the swashbuckling swordsman with Glamdring (and that too is canonical).

In any case, as the film moves toward its climax, Bilbo’s character spends his time doing what served the book perfectly, and serves the film so too: endlessly Refusing The Call (as Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey” structure would have it) and then hastily accepting it and Refusing The Next One… the refusals becoming briefer and briefer as Bilbo starts the process of growing into his greater place as the hero of this story as well as its heart. This is an arc that in my opinion needs three films for maximum believability: no one would have bought it in one film, and even two (to my way of thinking) would seem rushed. The main story arc, also — the return to the Lonely Mountain and the issue of dealing, both with the very intractable problem lying within it, and the other difficulties that will follow on that problem’s solution — also need time and space to stretch. So I think the three-film decision is the right one, and that things are proceeding as they should; and I’m intensely happy for the opportunity to sit back and watch Jackson & Co. get on with it.

Here are some scattered highlights that stood out for me:

Really big things happening. One of the great delights of film for me has always been its ability to show you something bigger than you could have imagined until you saw it unfolding in front of you right that moment. Probably what initially whetted my appetite for this kind of thing would have been the look down into the heart of the ancient Krell machine in Forbidden Planet. I’m always alert now for scenes in film that do this well, and there are a couple of scenes like this in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. One in particular involves a part of The Hobbit that I had completely forgotten about. Peter Jackson imbues this sequence with such a sense of sheer size and elemental threat that I got completely lost in it for some moments, torn between “Where the hell did this come from, I don’t remember this?!” and “Wow!”

Ian McKellen, doing what Ian McKellen does. In particular his scenes with Galadriel have something about them that’s unusually sweet without being cloying. There are other moments when some expressions of McKellen’s are given particularly close attention by the camera, with very good reason. It’s impossible to tire of watching such effortless mastery.

Smaug…what we see of him. Not very much, which doesn’t surprise me: I no more expected any significant view of him in the How-Erebor-Fell sequence up top than I would have expected seeing much of the shark, early on, in Jaws. But I have been waiting a long time for a dragon attack that properly shows the dreadful power and violence that such an onslaught should entail, and boyoboy do we get a taste of that here.

…Finally: surely I must have a few niggles? Yeah, a few, but they come very much from the fannish end of things. Chief among these: I’m not entirely sure about the characterization of Radagast. He smacks to me more of a T. H. White-ish Merlin than anything else, and knowing what we know about the Istari, I’m not sure that the affect of dotty absent-mindedness (with its overtones of “what-in-Middle-Earth-have-you-been-smoking-old-boy”) really works. Not to mention his, uh, mode of transport, which struck me as a bit on the Pythonesque side. …Well, maybe—if we see more of him—he’ll grow on me. (After all, enough things seem to be growing on him…)

But by and large, I had very, very few other problems with this film, and I’m looking forward to seeing it again sometime over the next couple/few weeks. This is, to sum up, as good an adaptation of The Hobbit as we could have hoped for: or rather, the beginning of as good a one. And we’re not done yet.

Because now, of course, the wait begins for The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug. For some people (myself included) it won’t come soon enough: next Christmas already seems far away. But I think the wait—and the wait for Christmas 2014—will prove to have been worth it. Looking forward, a time will come, I think, when these three films and the three LotR films that preceded it will be seen as a double trilogy, inextricably interwoven. We’ll see.

…One last note. Before seeing the film I almost entirely avoided looking at the early reviews from the trades and so forth: not for fear of spoilers, but because reviewers too focused on the bottom line can often affect one’s impressions in ways that don’t count—specifically, assessment of how the visual and verbal storytelling holds up. I allowed myself only one exception. I went and had a look at the review written by our old friend and colleague, Munich-based screenwriter and media maven Torsten Dewi (aka Wortvogel). I trust Torsten’s judgment, and was curious to see what he had to say. Now, having seen the film, I’m not surprised to see that he and I are on the same page as regards a lot of issues; and I commend his review to your attention (in rough Google translation if you’re not German-speaking).