Just posting this recipe here so that it can be found a little more readily. A tip of the virtual hat to the source on Tumblr, @locusimperium.

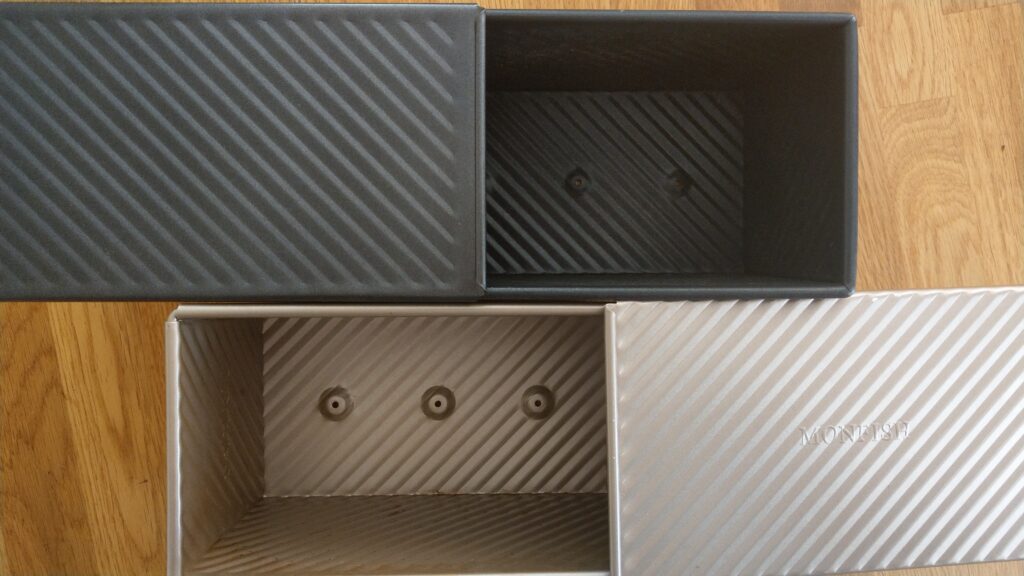

The ones in the above image were baked in an all-crunchy-edges brownie pan, but these bake perfectly satisfactorily in the recommended 9×12 inch sheet pan. They’re just fine plain, though the addition of a little ground cinnamon and cloves works well too.

Norwegian Christmas Butter Squares

- 1 cup unsalted butter, softened

- 1 egg

- 1 cup sugar

- 2 cups flour

- 1 tsp vanilla

- ½ tsp salt

- Turbinado / raw sugar for dusting

Preheat the oven to 400 degrees. Chill a 9×13″ baking pan in the freezer. Do not grease the pan.

Using a mixer, blend the butter, egg, sugar, and salt together until it is creamy. Add the flour and vanilla and mix using your hands until the mixture holds together in large clumps. If it seems overly soft, add a little extra flour.

Using your hands, press the dough out onto the chilled and ungreased baking sheet until it is even and ¼ inch thick. Dust the top of the cookies evenly with raw sugar.

Bake at 400 degrees until the edges turn a golden brown, about 12-15 minutes. Remove from the oven. Let cool for about five minutes before cutting the cooked dough into squares. Remove the squares from the warm pan using a spatula.

These tend not to hang around long, but if you think they might survive in your local environment for more than a couple of days, keep them in a cookie tin.