I’ve been a fan of Sherlock Holmes for many, many years. I don’t even really remember when I first started reading Arthur Conan Doyle’s immortal tales of the world’s first and greatest consulting detective, though it has to have been fairly early – probably when I was eight or nine.

There is nothing unusual about loving Holmes. Millions of others have done so before me, with good reason. What’s come up for consideration for me at the moment are the closely associated issues of what Doyle did to his most famous creation, and the fans’ reactions to what he did: with an eye to what’s going on at the moment at the BBC.*

SPOILER WARNING: though this blog is going to be fairly general, you should be warned: if you have NOT read the Sherlock Holmes stories up until now, and are also watching the BBC’s Sherlock simply as serial drama and have not seen The Reichenbach Fall as yet, then you’d better read no further until you’ve seen it and have come to terms with the result.

Anyway, I spotted this posting on tumblr this morning, and it started me musing.

you know I wonder if back in the day when The Final Problem came out Victorians were sending out letters with “Dear sir, have you read the latest Holmes story yet? I simply cannot handle it. I have cried an unseemly amount of tears. I cannot. Oh God.” and then there’s just a big ink scribble because keysmashing wasn’t an option

[little drawings of crying people in the margins]

When you write, naturally you hope that what you’ve written will have an emotional impact on the reader or viewer: the more profound, the better. But sometimes the profundity of the response can get scary — and this was as true in the pre-online world as in the hyper-interconnected literary world of today. Arthur Conan Doyle ran into the sharp end of this problem as his career was trending upward toward what would be seen by some as its peak.

Readers these days who’re more familiar with the written than the writer are often surprised to discover that Doyle didn’t think much of his Sherlock Holmes stories as compared to the historical novels that were his passion.** As so often happens in the writers’ world, Doyle had ideas about what his best works were — but the general readership and the critics had completely different thoughts on the matter. People went crazy for the Holmes stories, whereas Doyle’s historical novels tended to get fairly lukewarm reviews. (And today they are largely forgotten. If you can name even one, you’re either a Doyle expert or an unusually thorough reader.) This situation drove Doyle up the wall, though he didn’t routinely share that info with the reading public. With other writers – and he was friendly with lots of them — he was a lot more forthcoming about the disappointment. Otherwise he kept it quiet.

More annoying for him in the short term, though, was the fact that quite soon after the stories started making their initial splash, Doyle started receiving mail intended for Sherlock Holmes. Hundreds of letters came in containing praise, presents (though fortunately no cocaine), pleas for help, requests for interviews or autographs. Of course Doyle was here the recipient, many times over, of a backhanded compliment. Happy the writer (so other writers would say) who can create a character so compelling and rounded that people start corresponding with him, her or it as if he/she/it were real. Doyle was aware of the irony, and tried not to overreact; when he was in the mood, he’d sometimes get playful when answering Holmes’s mail “for him”, signing it “John Watson”.

But increasingly this confusion of identities became an annoyance, as not only readers but sometimes even critics seemed increasingly unclear on the difference between the writer and the written. One critic, the American poet Arthur Guiterman, wrote Doyle a bit of doggerel suggesting that Holmes’s opinions about literary detectives were actually Doyle’s:

Sherlock your sleuthhound, with motives ulterior,

Sneers at Poe’s ‘Dupin’ as ‘very inferior’!

Labels Gaboriau’s clever ‘Lecoq’, indeed,

Merely ‘A bungler’, a creature to mock indeed!

This when your plots and your methods in story owe

Clearly a trifle to Poe and Gaboriau,

Sets all the Muses of Helicon sorrowing.

Borrow, Sir Knight, but be candid in borrowing!

Doyle’s response in kind was polite but (to my ear) none too amused:

But is it not on the verge of inanity

To put down to me my creation’s crude vanity:

He the created, the puppet of fiction,

Would not brook rivals nor stand contradiction.

He, the created, would scoff and would sneer,

Where I, the creator, would bow and revere.

So please grip this fact with your cerebral tentacle:

The doll and its maker are never identical.

(When I read this I immediately heard BBCSherlock!John Watson’s voice saying, “He’ll outlive God to get the last word.” Doyle would have agreed that the line was right on the money as regards Holmes. But from the writer side, I also wonder if Doyle wasn’t a little annoyed here at Guiterman “not getting the meta”. A fictional detective twitting other fictional detectives for their failings as if he was a real person? That takes a special sense of humor, and a certain level of auctorial cojones. )

…Over time this kind of error, by itself, would have become irritating enough. But there were other stresses in place. Doyle was under increasing personal pressure as Holmes’s ascent into the position of one of literature’s great characters began gathering speed. Doyle’s father – with whom his relationship had always been problematic – was institutionalized and close to death from chronic alcoholism. Doyle’s wife’s health, always delicate, had become much more so since the birth of her first child. And the periodical publishers who’d been bringing his work out were terrified of anything happening that might slow down the output of their cash cow. After all, the appearance of Doyle’s name on a copy of the Strand Magazine would routinely boost its circulation by 100,000 copies. Once when Doyle returned to London from France on the cross-Channel ferry, he found every fellow British passenger he saw “clutching a copy” of the Strand… and he knew why. Just imagine yourself into his position for a moment. You’re famous. You’re rich, and getting richer. And you hate what’s getting you that way…

Trying to relieve a little of the pressure as gracefully as he could so that he’d have time to do the writing he did want to do while coping with the trouble at home, Doyle tried scaring off the Strand’s editors by setting truly insane prices for his Holmes work. But this tactic backfired: his publisher just whipped out the checkbook and paid Doyle his asking price. With his wife’s medical expenses to think of, and halfway through the building of a new house, Doyle gave in to the pressure… but with rather ill grace. He was feeling increasingly trapped by the necessity of servicing a character who was rapidly becoming perceived as more real than his creator. In 1891 Doyle wrote to his mother and said, in passing, “I think of slaying Holmes… and winding him up for good and all. He takes my mind from better things.”

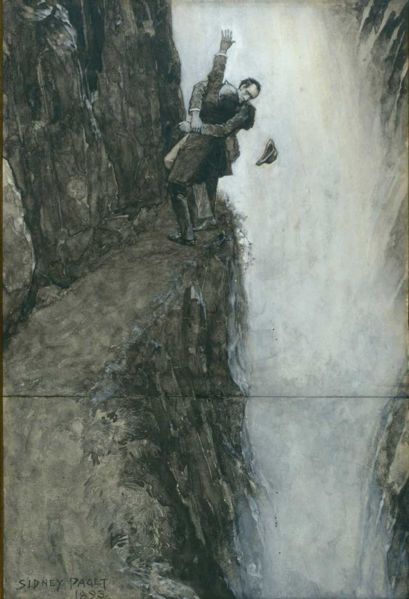

She wrote back and said “You won’t! You can’t! You mustn’t!” And for the time being, he didn’t mention the issue to her again. But while visiting Switzerland that year, Doyle was already location-scouting for the solution to what he hoped would be his Final Problem with Holmes. As early as 1892 he went walking among the clifflike ice-towers of the Findelen glacier near Zermatt, and discussed the impending character assassination in the abstract with his fellow walkers, one of whom argued against it earnestly but without making a dent in Doyle’s resolve. In 1893 he visited the Reichenbach Falls for the first time, and there he made his decision. “It was a terrible place, and one I thought would make a worthy tomb for poor Sherlock, even if I buried my bank account along with him.” Doyle headed back to England in August and started work on “The Adventure of the Final Problem”.

If there had been any last-gasp chance that Holmes’s death sentence might have been commuted – any last resurgence of Doyle’s ambivalence toward his troublesome character, for he admired him as much as he resented him — I think it was destroyed by the traumatic events of the following month. Doyle’s wife developed a severe cough and chest pain. A local physician was disturbed enough by this to refer her to a specialist in Harley Street, and Louise Doyle was quickly diagnosed with the form of tuberculosis of the lungs then known as “galloping consumption” – the worst form, normally quickly fatal. What kind of a blow this was for Doyle, who as a doctor should have recognized the symptoms long before, you can imagine. In any case, he wasn’t the kind to give up easily no matter how bad the diagnosis looked. The preferred treatment – for those who could afford it – was relocation to Switzerland for a prolonged “high altitude cure”. Some time between the last week in September and the beginning of November 1893, when Doyle and his wife arrived at the mountain TB sanatorium near Davos, the Consulting Detective and the Napoleon of Crime plunged down the Falls together, and Arthur Conan Doyle closed the book on Sherlock Holmes.

Or so he thought. The public responded with a massive uproar that amazed everybody, especially Doyle. Twenty thousand people canceled their subscriptions to the Strand. Hate mail arrived at the magazine’s editorial offices by the sackload. Thousands of people wrote Doyle directly, begging him to reverse Holmes’s death. It was said that people took to wearing black armbands in the street, in mourning for Sherlock Holmes (though there seems less evidence of this in the period’s press than there should have been, so this element of the overall story may be apocryphal). The death of the world’s first consulting detective was taken up by the wire services and reported all over the world as front-page news. Obituaries for Holmes appeared everywhere. Petitions were signed and “Keep Holmes Alive” clubs were formed. Not since the demise of Dickens’ Little Nell had a literary death had such powerful effect right across the whole language area of its readership, and not since then had a fandom made itself so obvious in its grief. The like would not be seen again until the deaths of Spock and Dumbledore.

Doyle resisted the pressure as best he could, thinking it would surely taper off after a while. But it was unrelenting, continuing for years: his creation had already become more powerful than he could possibly have imagined. In 1903, having in between reluctantly written and published “The Hound of the Baskervilles” (as a backstory “untold tale”) to huge acclaim, Doyle finally relented and wrote “The Empty House”, in which the Final Problem was revealed not to be as final as previously thought. Which leaves us looking toward the present day, and the BBC’s Sherlock.

The structure and chemistry of the situation is naturally different here, as the new series is both restatement and celebration of the original, wittily and unflinchingly updated for the 21st century. Now, in 1893 almost no one knew what Doyle was planning to do to his creation at the Reichenbach Falls (this despite the news having been sneaked in a magazine called Tit-Bits the previous month: possibly the readers dismissed the news as impossible). Obviously things are different now. Yet over in Tumblr — that great hotbed of unbridled and completely indulged fandoms — there’ve been a lot of messages over the past couple/few weeks either begging DON’T SPOIL ME, or foreshadowing the inescapable results sans spoilers but with a sort of gloomy yet desperate relish. (In reaction to the DON’T SPOIL MEs I’ve seen a few astonished queries along the lines of “WTF, haven’t you read the stories?!” — and I keep having to remind myself that yes, it’s entirely possible that lots of people haven’t. Or haven’t even seen the excellent Jeremy Brett Holmes of the 80’s. Brett has until now been the definitive Holmes for me. Now I find myself strangely torn.)

But there’s no question that the fans are as attached to Sherlock (and to John Watson) as ever the readers of 1893 were to the version in what Holmes fans were the very first to refer to as “the Canon”. And they have good reason. It certainly helps to have such a strong cast, with such range, and scripts as tough-minded and elegantly constructed as these have been. But again and again you have to come back to the strength of the actors. Writing the last twenty pages of the “Reichenbach Fall” script must have been a bitch, and probably a bitch again and again, as it got hammered on to make it as perfect as it could be. But even a strong script can be deprived of a lot of its striking power by bad acting. Fortunately “Reichenbach” had no such problems, and if we got down to it, doubtless Peter and I could argue for hours over whether Benedict Cumberbatch’s or Martin Freeman’s performances were more powerful or heartrending in those final scenes. Probably it’s a great timesaver that we don’t roll that way: we’re quite happy to just get on with business while waiting for 2013 – there being a peculiar pleasure in watching another writer do what he does uniquely well. (And that’s as far as I’m going in the analysis direction on this episode or this series. Enough electrons will splatter themselves across the screens of far better or more driven analysts than I in the days and weeks to come.)

Elsewhere in the online world, though, and particularly on Tumblr, the grief is breaking out all over. And it’s wrenching, some of it: despite knowing that Sherlock miraculously (“one more miracle, Sherlock…”) did not take the fall. All you have to do is follow this link to see some of the more recent reactions. Some people are philosophical. Some are incoherent. Some threaten to assault the writing staff. (And this too has its resonances: think of all the hate mail that poor Doyle had to deal with, not to mention the one report of the lady who hunted Doyle down in the public street and clouted him with an umbrella.) Many of the postings are eloquently fraught. There is a lot of Figuring It Out stuff going on. And what fascinates me most is that, in this somewhat-alternate Canon, the grief is fairly evenly split between Sherlock and John – and not just among those preoccupied with the slashiness of the pair. (“Bachelor? Bachelor? Confirmed bachelor??!” …Never let it be said that Moffat and Gatiss are afraid of committing unabashed and wickedly cheerful fanservice when it bloody well suits them.) Friendship and its durability, and sacrifice and its price, are the main themes being discussed. Whatever else can be said about a TV show, any entertainment that gets people to discuss such issues in depth and detail is surely worth watching.

Meanwhile: I’m looking forward to sitting down in a couple of days and reviewing the episode, shot by shot, and doing some Figuring It Out stuff myself: for it’s always a pleasure to watch professionals at work, while trying to second-guess them a bit.

And who knows… maybe my avatar needs a black armband.

ETA: Once again at Tumblr, see also this charming development — not just the fandom speaking, but a new metafandom: Believe in Sherlock (Doyle was friends with J. M. Barrie: the creator of Peter Pan would probably also be charmed.)

*Disclaimer: yes, I’ve written for the BBC. And I had a great time.

**Most of the biographical material above comes from Martin Booth’s excellent bio The Doctor, The Detective and Arthur Conan Doyle. It contains a ton of info that isn’t found elsewhere, and I heartily recommend this biography to other Holmes fans who’re looking for more information about Doyle’s complex and busy life, and the way Sherlock Holmes affected it. In particular, this bio was the source for some background information that turns up in On Her Majesty’s Wizardly Service / To Visit The Queen.