I thought this had been removed from YouTube. So happy to be wrong. 🙂

Category:

Star Trek

Or it’s corny this year, anyway. From Reuters:

A British fan of the cult TV show “Star Trek” has boldly gone where no man has gone before and created a giant maize maze dedicated to the program.

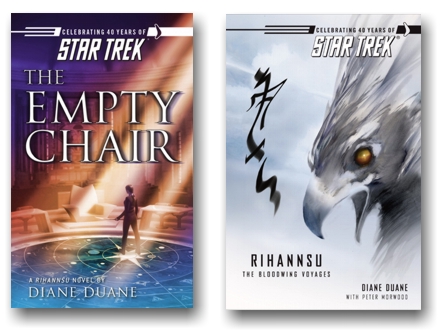

…I foresee many, many such strange things happening this year to celebrate the 40th anniversary of Trek. (Such as the last of the Rihannsu books coming out.)

Now playing: Christopher Cross – Ride Like The Wind

Older Posts