A note as we begin: Mostly this blog (per its name) is a place I talk about just about everything but writing. Over time, though, people have started asking me questions about the business and practice of novel- and screenwriting, and I’ve been thinking about where to put the answers. Finally I figured something out. So this post—along with various others on writing that have wound up here or on my Tumblr over time—will be colocated at the new FicFoundry site when it goes live in Q2 of 2024. Eventually this post will be redirected from here to FF.com… just so people know.

First of all: The tweet from Rebecca F. Kuang that started off the thread is here.

wait can someone who isn’t a pantser actually explain themselves? how detailed does your outlines get? do you really know the sequence of and content of every scene ahead of time? how you figure out smaller plot threads before you’re ~in~ it?

— Rebecca F. Kuang (@kuangrf) July 24, 2020

Then adding:

haha well what i’m most curious about is how you can “feel” the story’s tone/heft/urgency and connect with the characters and their plight from an abstract outline? i’d like to plan more, but i have a hard time thinking from a birds eye view

— Rebecca F. Kuang (@kuangrf) July 24, 2020

…What followed was an off-the-cuff recreation of an ask-box answer on Tumblr that goes back a few years (so if you follow me over there and this seems familiar to you, you’ll know why).

…Let me say from the outset that from the beginning of my career as a professional writer I’ve always been a plotter. This started out, not as an instinctive preference or a random developmental thing, but as a mere fact of life—because after I sold my first book I went straight into screenwriting. And if you’re writing for series TV, pantsing is not a thing that’s allowed. Your story editor (or producer, or showrunner, or head-of-story) needs to know immediately and in detail what the paying customers are going to be getting.

Therefore, as a submitting freelancer (for this was before the “room” concept was invented), the first thing you’d usually do when not pitching verbally*— or else having just done so—would be to submit a précis [very short description of characters and plot, 2-3 pp] or premise [same but longer: 8-10pp] for approval. The details of what kind of paperwork were required might vary slightly from production house to production house. But until something pinning down what happens in the story (and usually also the order in which things happen) gets turned in and approved, you won’t be commissioned to do the work.

After that, routinely—in animation (and in later live-action drama)—you’d go on to a full outline. Depending on the length of the script to come, and how much money is riding on the work, this might be anywhere between 15 to 30 (double-spaced) pages. And then, assuming that was approved, you’d be allowed to progress to the the screenplay stage.

So: multiply such a set of events by twenty or thirty scripts and you can see how with this kind of work history, if you’re not already an outliner, you’re likely to get hardwired that way in a big hurry. Be the format short or long, just about everything involved in film or TV production has some kind of outline associated with it. So by the time I started my second and third novels in the mid-’80s, I was already pretty much locked in as a plotter/outliner for life. And it’s worked quite well for me.

As regards the process of constructing an outline: C. J. Cherryh taught me a method which I now think of as “the Shopping List Technique” and which has served me well for the last three and a half decades or so.

Simply this: you sit down and make a list of the ten things that have to happen in your novel—the character actions or physical events without which your story simply cannot occur. Then, when you’re sure you’ve got pretty much the ten major “event beats” or character issues nailed down, you break each of those ten things into its own section and list the ten things that have to happen surrounding that event or supporting that character action. You take your time over this work, because this is the skeleton of the body of your work to come—the physical / emotional / action structure on which you’re going to build your novel.

And rather than proving restrictive, getting scene-by-scene detailed at this stage of the work is incredibly freeing. Having this solid scaffolding to build on lets you turn your full attention to character business and interaction… because you already know who’s got to go where and what they’ve got to do. You can now wallow in Drama and Spectacle and All The Feels, and not have to waste time sweating the workaday details of the who-goes-where-and-what-happens choreography.

You have, in essence, drawn your road map. Now you journey. If (along the way) you find that the road wiggles in ways that work better for your story than the original ones—then, fine, you redraw that part of the map. But the map as a whole preserves for you a sound basic representation of your final destination and desired result; something you can fall back on in need, or if your focus shifts without warning.

Let me spend a little time here dealing with the actual process of outlining the way I do it. (And naturally I’m going to preface this with the caveat that just because this works for me is no reason for anyone to take this method as any kind of gospel. Finding your own way is a vital part of the Writer’s Journey. But if some part of this seems to work for you: steal, adapt, run off with the goodies! Others shared what worked for them with me: it’s a pleasure to pay that forward.)

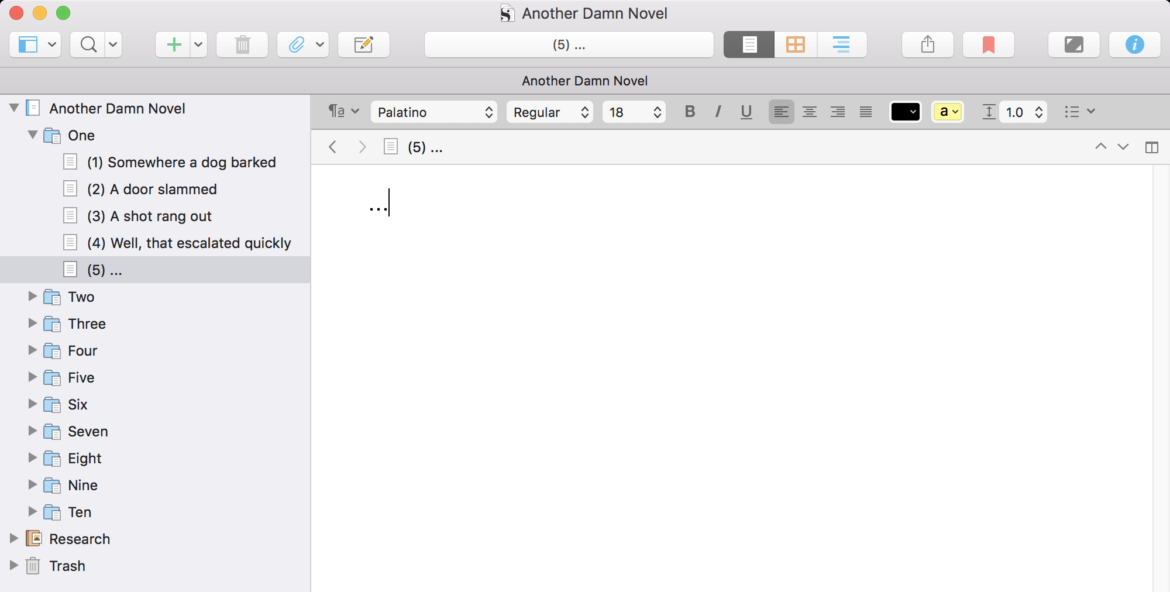

Those lists of ten-things-broken-down-into-ten-more-things start out for me as incredibly messy scribblings on the fabled Magic Note Paper and then get typed into whatever outline processor I’m using at the moment. …Unfortunately I have none of those messy pages to show you, because as they’re transcribed, I destroy them to keep from confusing myself later as to whether that material’s been handled or not. …These days, anyway, the lists go into Scrivener …and the result is likely to look something like this.

…The formal breakdown-of-tens may or may not remain static or be visible in such a document at any given point due to sections or bits of business being combined or telescoped into one another, and the numbers of beats and sections may change without warning. This is perfectly normal for novel outlining. You discover as you start more closely investigating / filling in the Tree of Tens that some sections need different contents, lengths, or rhythms.

This is the “filling in empty spaces on your map” department, where (for me anyway) the real exploration and revelation of the story happens. In the outliner, scraps of scenes, dialogue, and descriptions of business can now get slotted in. (Scrivener makes it a lot easier to organize and rearrange these than it used to be in a Word document… but it doesn’t matter in the slightest in what kind of word processor you’re doing this. Just break the ten “big sections” into divisions big enough for you to comfortably work in.) In these separate sections, action can be amplified or refined: motives and character interactions can be expanded and explored.

In my case, the outline sections and subsections start to contain long text passages that arise to be written while considering the subsection titles. (Considering them as prompts may be helpful.) Or they may just contain very linear notes about what has to happen. Or both. And this part of the outlining can go on for a good while, as it becomes clearer what material is needed in the story and what’s surplus to requirements.

This business of describing what has to happen—in the strictly linear sense—will normally be pretty much complete before I’m ready to submit anything to an editor. It may be helpful to think of what we’ve been discussing so far as a much expanded or differently-structured version of what a scriptwriter might consider a beat sheet / beat outline. But also for consideration here should be what kind of outline you’re going to send to your commissioning editor when you’re querying and they ask you for a specific kind of “partial”, the traditional “three-chapters-and-an-outline”.

Around here, this sort of outline gets handled in different ways. The editor may have worked with me before and may already be familiar with how my outlines reflect the finished novel, even though they may not be broken out into chapters. Those editors will usually get an outlined description of events that’ll be heavier on the emotional context. Example: the premise-cum-outline I sent Harcourt for The Wizard’s Dilemma. This is on the short side because I knew my editor was perfectly familiar with the first four books in the series.

On the other hand, one may be pitching to an editor one hasn’t worked with before, in which case breaking the outline clearly into chapters may be smarter. This version of a novel outline was what went to my editors on what became The Book of Night with Moon. Since in this case the editors already had chapters 1 through 3 as part of the pitch package, what they then got was the outline for the book onward from chapter 4. (You’ll have to just imagine the first three chapters. Essentially, a trio of cat wizards pick up an unexpectedly punk-ish apprentice.)

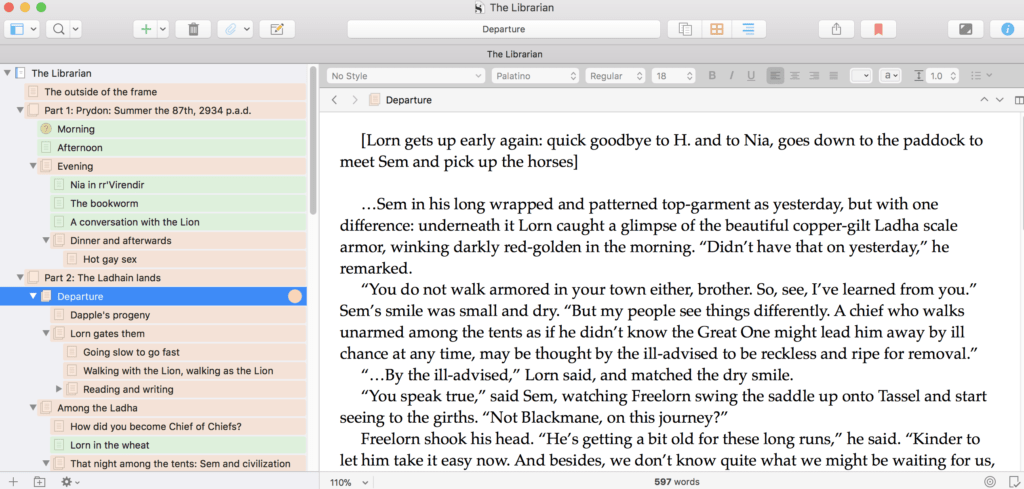

Now, the linear-looking stuff that you saw in the Scrivener screenshot above, and the outlines that went to the editors and sold the books, are obviously very different. The latter sort of outline is synthesized from the former. But it’s important to do so with the characters’ emotions, and the emotional content, fully in place.

And this is where the problem that @kuangrf was mentioning in that earlier tweet can easily be handled. While the List-of-Ten-Tens method is extremely effective for handling the mere business of physical action (“A goes to B, kills C, flees the country”), it’s just as effective for structuring the flow of emotional events and interactions among characters. (“X feels terrible about what they’ve done, thinks that though it scares them they need to consult with Y about how to approach Z to make amends…”) I routinely include the two “streams” in the same section, particularly because for me they need to be driving each other; it seems inevitable to me that what you have to do will influence or drive how you feel about doing it. So no need for an outline to be dry or abstract! In fact it works better (I think) if it’s not. The more emotional juice you can pump into it, the more will ooze out when the reader bites.

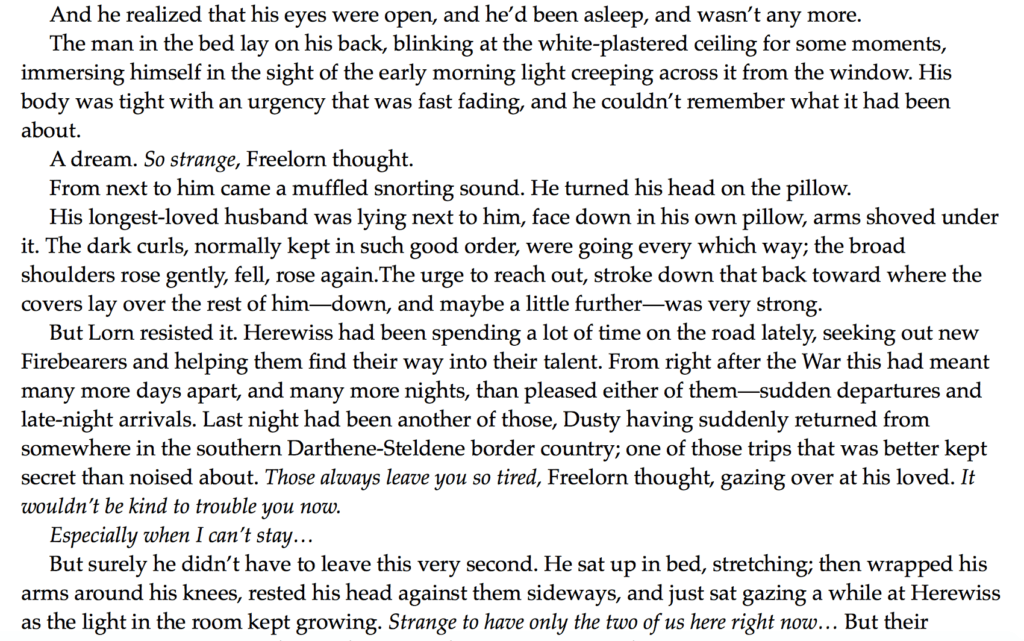

For example: the very first of the ten-of-ten for Tales of the Five #3: The Librarian (which we’ve been looking at in the screengrabs) said “[King] Freelorn has an unnerving dream that tells him he’s got to go on a journey…”. And the first of that chapter’s ten subsections simply said “He wakes up too early and spends a while looking at [his husband] Herewiss in ‘missing you already’ mode: then gets up, does his morning stuff, and goes to work.” And the first time I sat down to work on that chapter, I got this right back from that section’s prompt:

…So you get a sense of how this goes. Take care to bake the emotion into the outline along with the physical action / broader thematic structure, and it will do it nothing but good. And make your job easier.

…There the thread pretty much ended. There’s just one background / thematic thought I want to add.

I think there’s too broadly spread-about (and often unquestioningly accepted) a narrative that says that outlines are somehow creativity-deadening or -defeating, or will suck the life or spontaneity or whatever out of your prose writing. Let me qualify this assertion immediately by saying that I understand perfectly well that there are writers for whom this mode of novel management doesn’t work; that they’ve attempted it, and feel that valuable creative energy is lost to them in the structuring process. That experience must be respected. Whatever you do that works for you is valid.

But I do feel that a lot of the time, outlining isn’t given a fair shake by people who’ve never tried it and just don’t like the sound of it because it doesn’t sound fun enough. And what troubles me most about this is that too much unexamined advocacy for the Yay Let Us Be Utterly Free And Unfettered In Our Creativity school of thought** is depriving a lot of new writers of a really terrific tool that can keep them from doing something that over weeks and months and years is truly terrible: wasting creative time.

For my money, possibly the single most poignant line in Avengers: Endgame was Tony Stark saying to his dad (in both bittersweet and quite ironic mode, considering story continuity) that “no amount of money ever bought a second of time”. When you’re early on in your creative career, and possibly have your best energy levels at your command, it’s easy to feel as if all eternity is before you… as if blowing a week or a month (or six months or a year) on the free-and-unstructured development of a project is no big deal. But later on, in both the short and long terms, you may find yourself revisiting that attitude with considerable regret. And the paradox attached to the resistance to outlining among new / just-getting-started writers is that this is the stage at which it’s most likely to be useful to you. From that earlier post on Tumblr:

At the very beginning of this process, outlining is the easiest and most straightforward way to go, and eliminates the chance of you wasting time by running down a lot of blind alleys and getting caught up in choices that you don’t need to be trying to make at this stage of the operation. Later on, as you get better at this setup process and more confident about it, you can dump outlining if you find yourself disliking it and are able to produce reliable similar-quality results without it. For now, though? Help yourself out by making yourself a shopping list until you can be more certain you won’t forget the stuff you went to the store for.

So let an older writer just say here to the younger ones, the newer ones: We want more of your work, and of your best work: not less. Outlining might work for you—might indeed save you surprisingly large amounts of time, uncertainty and frustration that would otherwise be wasted in waiting for the stars to align or the Muse to arrive or whatever. Just give it a shot, okay? Please and thank you.

…So that’s that. Thanks for reading. And believe it or not, I actually do have to go work on the outline for something at the moment. So if you’ll excuse me? …And enjoy your day.

*In animation writing, where I broke into screenwriting, writers were routinely invited to pitch in writing first—which is not how it was done in live action writing. Writers’ Guild rules then required that you pitch to the production staff in person.

**Please don’t mistake me here. I’ve written in that mode often enough, and it’s utterly fabulous when it’s working correctly. But over the long run, over a career, with deadlines and other people’s jobs riding on your output turning up in a timely manner, depending on it always to work is dangerous. C.S. Lewis says somewhere that the greatest illusion in which creative people indulge themselves is that what they’ve done once, they can do always…

Also, for those who’ll inevitably ask: yes, I’ve tried pantsing! In fact I’m doing a pantsing project right now. And it is LIKE BREAKING ROCKS WITH MY HEAD. Excruciatingly difficult and painful! But I committed to [REDACTED WELL-KNOWN WRITER] that I’d do this to give the concept a fair shake… so I will be following that project through to the end. (It’s this one. It is entirely possible that I’ll fail at this in ways that have never been seen before, but for fairness’s sake it has to be done. Because I can’t fairly ask people to do something, i.e. attempt the Completely Different Method, that I’m not willing to do myself…)