#FolkloreThursday at Twitter is looking a little serpentine today, and for some reason this old Swiss folktale came to mind.

A good while back, more or less around the end of the eighth century, Charlemagne was King of the Franks: and he had a castle—or more properly speaking, in that period, a nice little fortress—down in the Zürich area.

Charlemagne had a reputation already for (when he wasn’t rampaging around the local battlefields) being quite interested in the concept of justice for both high and low. The story tells us that he commanded a pillar to be put up outside his castle, and a bell hung from the pillar: and whoever felt that an injustice had been done them could come and ring that bell, and servants would come and conduct them to the King, who would hear their case and do justice upon them.

So one day the King was eating his noonmeal when the bell began to ring, and the servants went out to see who was ringing it. But when they looked, they couldn’t see anyone standing there. This puzzled the servants, and they went back inside.

No sooner had they done so than the bell began ringing again. Out went the servants, and again—from the battlements, or the gates—they saw nothing. And they went back in and reported this to the King, who was a little bemused by the news.

Once more that bell started ringing. This time someone actually went down to get a closer look, and what that servitor found was that a snake had wrapped itself around the bellrope and was throwing all its weight downward again and again so that the bell would ring. The servant, somewhat disturbed, tried to get the snake to go away, or at least to stop ringing the bell: but nothing would make it desist.

(This is the point where scientific inquiry rears its head to answer the question “What kind of snake was it?”. Probably it was one of the local species of viper, Vipera aspis maybe, rather than just some passing black snake or corn snake or whatever, which the servants would have dispatched in short order.)

The news of what the servitor had found was brought to the King, who said, “No, don’t try to chase it away. If it desires justice, justice it shall have.” And out he went, in the middle of his lunch hour, to see this wonder and try to get to the bottom of it.

When it saw him coming, the snake let go of the bell rope, dropping to the ground, advanced toward the King, and then stopped and bowed its head to him. Charlemagne greeted the snake and said, “You have called me to deal justice for you: here I am. What do you need?”

The snake promptly turned tail and led the King and his servitors away toward the nearby woods, pausing every now and then to look behind it to make sure that it was being followed. Into the woods it led the King and his retinue. When the viper stopped by a tree near a little stream, the King bent down and saw among the tree’s roots a nest of the snake’s eggs. And on that nest, there was squatting a large and malevolent-looking toad, preventing the snake—plainly a mother snake—from getting at her children-to-be so that she could properly care for them. Even as the King and his servitors watched, the snake struck the toad with her fangs, trying to drive it off. But the toad sat there and seemed no whit affected by the viper’s poison. And the mother snake looked at the King as if to say, “See?”

The King regarded this situation with some disquiet. Everybody knew that when a toad hatched out cockerels’ eggs, pretty soon you were knee deep in cockatrices, which were an incredible nuisance to get rid of. God only knew what would happen if a toad was allowed to hatch out snakes‘ eggs. And anyway, the mother was being prevented from exercising her parental rights. So the King said to his servants, “Get the toad off her nest and burn it for its crime.”

This kind of immediate decision was well in line with Charlemagne’s normal management style, which had long been known to be on the robust side—the man himself being a little weak on the concept of proportional response. In any case, the toad was taken away and thrown in a fire, and that was that.

The snake bowed again to the King, plainly in thanks, and coiled herself back up on her nest; and the King bade her farewell and went back to his castle, doubtless thinking that he could dine out on this story for a week or so at least.

That wasn’t the end of the business, however. The next day, at lunch, the King and his courtiers were discussing local politics or whatever when the guards down at the end of the banqueting hall suddenly looked very surprised, and between them and up the length of the hall, here came the mother snake. She paused before the royal table and bowed to the King.

“Greetings, Madam Serpent,” said the King. “What brings you here today?”

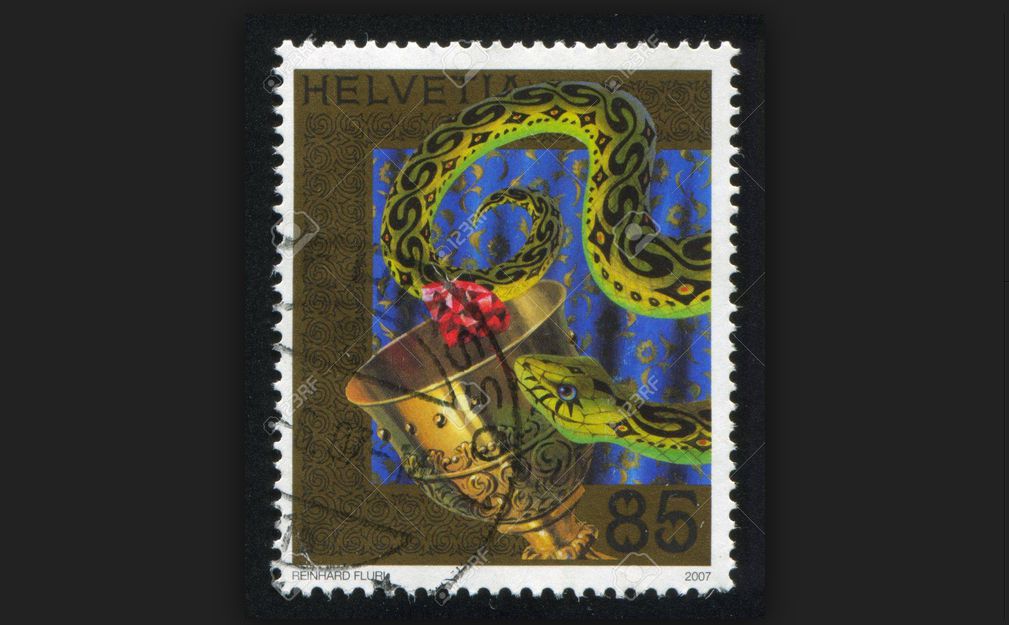

Without further ado the viper slithered her way up onto the King’s dining table, carefully sliding toward him among the plates and cups. Presently she wrapped herself around the King’s own cup, which was empty at the moment (because the butler whose job was to keep it filled was standing behind the King’s chair and freaking out at the concept of getting too close to a very poisonous snake). And the viper leaned up over the cup and opened her mouth, and revealed that in her mouth she was holding a great glittering jewel, which she dropped into the King’s cup.

Then she bowed her head to the King and took herself away.

Charlemagne took the jewel out of the cup to examine it, and everyone looked at it in wonder. It was delicately graven with strange symbols, and everyone wondered where the viper had found it. But it seemed like any questioning would be useless—whatever else she might have done, the snake had shown no inclination to speak. So the King caused the royal jeweller to be sent for, and gave him the jewel with orders to have it set into a ring. This ring he gave to his Queen, Fastreda, as a priceless curiosity.

Now, it was not as if Charlemagne did not already love the Queen. But his courtiers started to notice that after the day the Queen began to wear the jewel, the King’s eye never again strayed to the other beautiful women in his court (and his eye was known to rove, if no other part of him did.) His affection toward her became much more marked: the two of them were rarely apart. And everything was very well between them for years… until the Queen became ill and it was plain she was about to die.

Apparently Fastreda suspected something of what was going on with her ring: its virtue seemed to be that the one who gave it to you would have their love fastened exclusively upon you. She feared that the jewel’s power might somehow be used against her beloved lord and husband should it be taken from her after her death. So in a moment when she was alone, she slipped it into her mouth; and soon after, she died.

The King was inconsolable at her death, and would not allow her body to be put in the ground… took it everywhere he went, and kept it in his bed at night. This was seen as peculiar at the very least: everyone became quite concerned for the King’s mental health. And some days after the Queen’s death, the good Archbishop Turpin—who also took his job quite seriously when he wasn’t plunging around battlefields hitting people with his ecclesiastically-sanctioned mace—spent all night in the castle’s chapel, asking Heaven for advice. And sure enough, eventually he nodded off, and in his dreams the Blessed Virgin appeared. She said to the Archbishop, “Search the body and you will find what’s at fault.”

Turpin woke up intent on doing the Holy Virgin’s bidding. Quietly he crept to the King’s bedchamber, where the King had fortunately fallen asleep, exhausted by his grief. And Turpin searched the Queen’s body and found the jewel, and removed it.

In the morning, when the King woke, he looked sadly at the Queen’s body and said, “I think it’s time we buried the Queen.” And everyone was very relieved to hear this. But the moment the King laid eyes on Archbishop Turpin next, he made it plain that he wanted Turpin close to him all the time.

It took the sagacious Archbishop very little time to put two and two together. Royal business soon enough took the King north, and perforce Turpin was brought along with him and the rest of the Royal retinue, and the King spent every moment he could of every day in Turpin’s company, even (some say) requiring him to sleep in his own bedchamber. And finally the royal progress brought them to Aachen, a spa town with hot springs where the King liked to winter.

Once they reached Aachen and moved into the royal lodgings prepared for them, the King organized banquets and hunts and entertainments, and all through every one of them Turpin was required to be in the King’s company. But finally he saw his moment. During one hunt, as evening drew near, Turpin managed to get himself separated from the royal party and “lost” in the woods. With all the speed he could muster he made his way to the nearby shore of the Wehebach lake. There on the shore Turpin pulled out the ring that held the viper’s jewel and cast it far out into the waters.

Eventually Charlemagne, who had been looking for his friend, found him there by the water.

“Feeling better?” said Turpin to his friend.

“Much,” said Charlemagne. And he looked out over the water. “I don’t know what it is,” he said, “but there’s something I really like about this place…”

And one way or another there must have been, for Charlemagne wintered there every year until the end of his life: and there he died and was buried, in the little cathedral he built in Aachen (or Aix-la-Chapelle as the French has it) . Many people have suggested all kinds of reasons for this choice of the great King’s “favorite city”: political expediency, a central location for his pocket empire, a fondness for hot water all year round. This late in time, who can tell?

And in the meantime, the Swiss have put the mother snake on a stamp, and the Swiss are very serious about their philately: so who knows? Perhaps once it was all once true…