Every now and then I’ll be minding my own business and doing my work, and then suddenly, without warning, the urge to commit fanfic will strike.

Mostly I ignore it because I have so many other things on my plate. But every now and then comes a day when it can’t be ignored. The story that appears here was the product of one of those days.

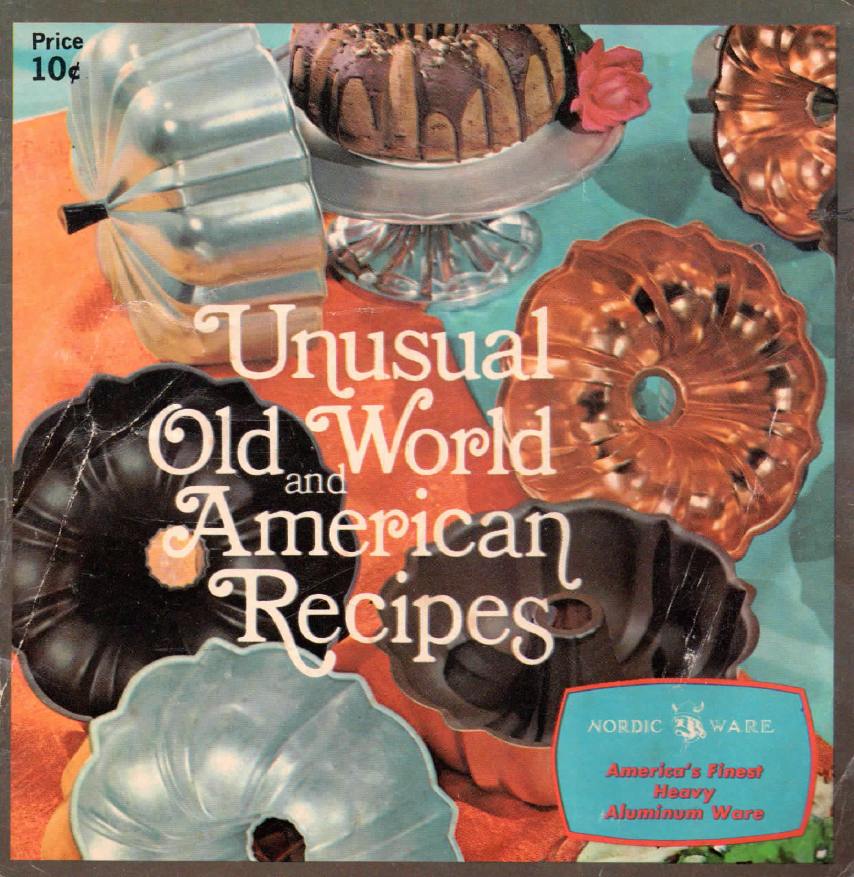

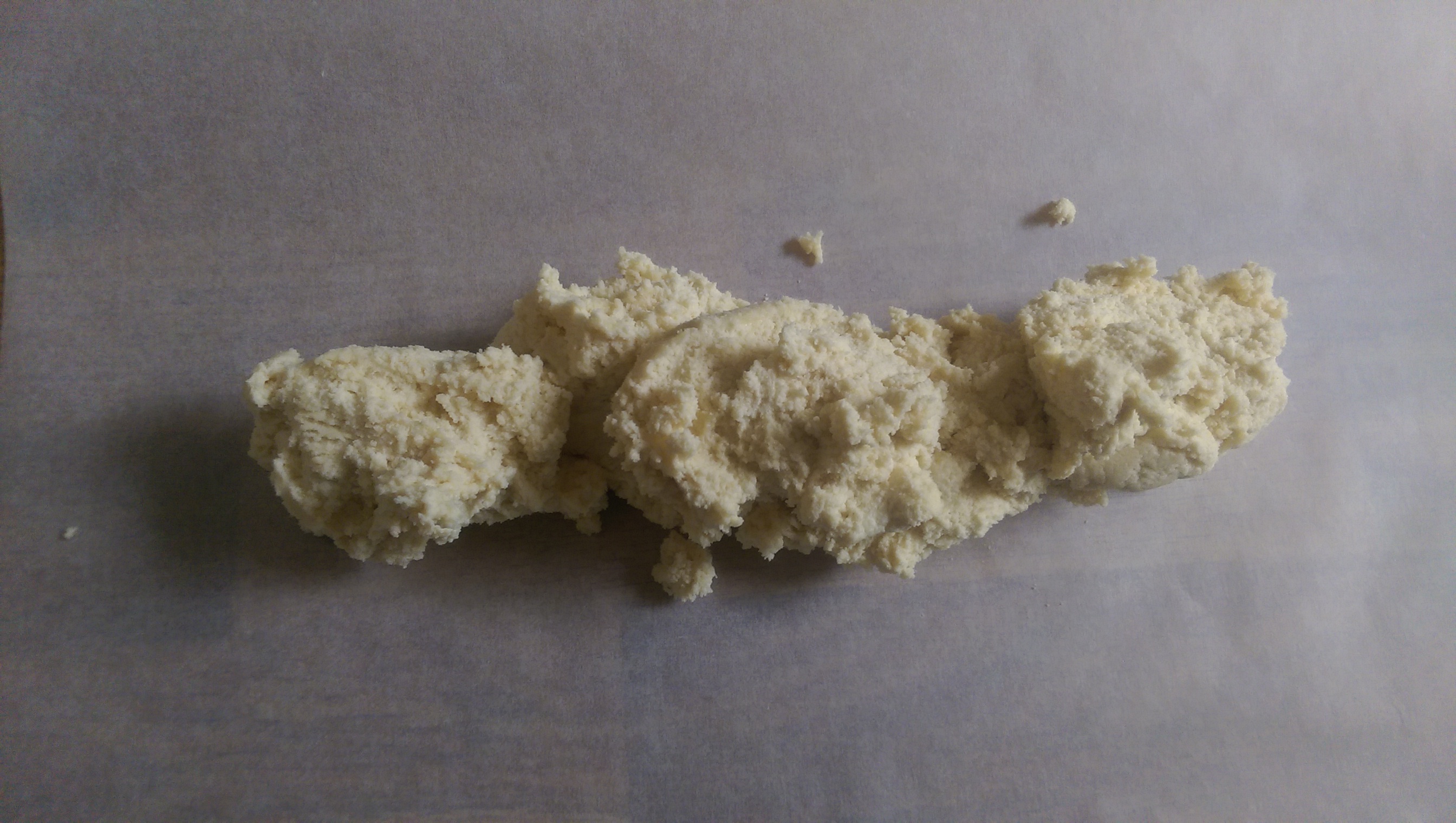

When I was making this cake back in 2012 or so, the phrase It was dark, dark at heart… whispered itself in my mind’s ear. Over the days that followed, that phrase fought its way out and dragged a whole bunch of other words behind it. When it was complete, I let it out into the world on my Tumblr, and then (for reasons I still can’t remember) took it down, and then (just because I damn well felt like it, I guess) put it back again. And here it is now, to go with the cake recipe (just reposted for National Chocolate Cake Day).

Stories satisfy the writer in the aftermath of their creation for all kinds of different reasons. But right now this one makes me happiest because it nailed down (a year or three early) a bit of personal headcanon which has as of Sherlock season 4 been proven true. Otherwise, it also nails down memories of a happy time — when I spent a while in its featured locale while working on the first draft of Stealing The Elf-King’s Roses — and incidentally, there near the source of the Rhine, took a phone call that heralded what was about to become a five-year development process culminating in the miniseries Die Nibelungen*. It was kind of a magic time, and one I enjoyed preserving here… while nodding in the direction of one of my oldest fannish loves, the great Canon, through one of its newer versions.

And the cake’s pretty good, too. 🙂

Once upon a time, in somber mood, Mycroft Holmes asked Dr. John Watson what, in the light of the qualities of Sherlock’s mind and certain piratical tendencies, one might deduce about his brother’s heart. He asked this – so John thought later – seemingly with no great concern that any similar question might be asked about him. And indeed few men, or women either (Anthea aside) would be correctly positioned to either ask or answer. Sherlock, if the subject arose, would probably roll out the heavy-gauge snark and suggest that in his brother’s case, the way to his heart is almost certainly via his stomach – but due to the first organ’s tiny wizened size, something’s apparently gone wrong with the connections to the second, so that incoming material inevitably continues through the system in the normal boring fashion…hence Mycroft’s never-ending diet.

When this issue comes up in conversation, as with Sherlock it always does, Mycroft mostly just sighs: because the nature of his job mandates that he keep himself in proper condition to do it, and this issue has accordingly been folded into his personal security and self-defense portfolio. Other aspects of that portfolio are slightly less controversial between him and Sherlock: the invisibly armored black cars, the overarmed, overtrained drivers, the redoubtable Anthea and her watchstanding colleagues – about whose gifts even Mycroft is glad to relax into don’t-need-to-know mode. He does know that the Double-0’s (though not necessarily their watchful Quartermasters) tend to exit the soi-disant “International Exports” building en masse to avoid embarrassment (theirs) when they see Mycroft’s Angels coming in to do their yearly sidearm and unarmed-combat certifications with their normal no-testosterone-needed competence.

And then of course there’s Mycroft’s final line of defense, which almost no one suspects because that umbrella looks so very, very slim. (The inevitable rumors have made the rounds about hidden ricin pellets, but these are unfounded.) Naturally, Anthea knows what the umbrella’s hiding. Equally naturally, Sherlock long ago deduced what’s in there. And in his very mellowest moods – stretched out beside the midnight fire and cradling the violin, with John cozily dozed-off in the opposite chair – the world’s only consulting detective will sometimes allow himself a tiny, secret smile when the issue comes up for consideration. If he was able to speak a civil word to his brother without arousing his suspicions, he might even some day admit to being obscurely touched that Mycroft carries with him everywhere, invisible in plain sight, a perfectly tempered, razor-edged reminder of the long golden childhood afternoons when they played the Pirate Game together with shouts and sticks, before moving on to edgy adolescence and beginning to routinely drive each other mad.

About the diet, though, Sherlock unfailingly rags Mycroft without mercy: and it’s really most unfair, because it does work. Mycroft has for some years employed the Rotation Diet, which after a truly Holmesian level of assessment he eventually determined was the most effective tool for his own purposes. It sets a rational intake and (surprisingly light) exercise baseline, does a good job of fooling his metabolism into burning more calories than it should, and allows for the inevitable ups and downs of his work life: and in particular it allows for “free weeks” during which one may safely go a bit off the rails.

This is important to Mycroft, because he knows that power, especially when it leans so close to the absolute, must be constantly tested to prove that its foundations are sound. Its bearer’s weak points must be laid bare, examined, reinforced, then stress-tested again. And for Mycroft, cake is a weak point. It would be irrational to deny it.

So when it comes time for him to do the quarterly assessment of his strengths and his ability to manage his weaknesses, not just any cake will do. He requires something truly dangerous, a veritable Moriarty among cakes… so that his mettle can be tested, and proven not wanting, at the highest possible level. And finding the worthy antagonist for such tests has occasionally proven as much fun as the test itself.

Now, Mycroft has more than once had reason to be pleased that he can count among his closer acquaintances a gentleman who occasionally serves a neighboring European government in a capacity similar to Mycroft’s. This gentleman – whose codename is “Colin” – while confabulating with Mycroft late one night over brandies at the Diogenes, let slip (in that particular sort of casual manner meant to suggest to his counterpart that the matter’s not casual at all) that he knows a woman who has a close connection at Confiserie Sprüngli in Zürich.

This made Mycroft’s eyebrows go up with interest. That choice place near the lakeside end of the Bahnhofstrasse, under the shade of the linden trees, is known and honored among chocolate lovers the world over for the suave intensity of its productions; and the best of its cakes, the truffle cake, is truly a thing of beauty, if a bit lightweight for Mycroft’s requirements. However, Sprüngli proper, as it turns out, was not the epicenter of his colleague’s interest. Colin told Mycroft of how in a moment of weakness (possibly fueled by a bit too much after-hours kirsch), the Sprüngli confectioner shared with Colin’s female associate a tale of something extraordinary, a secret hidden away among the mountain peaks a couple hundred kilometers south: a link to something in both his, and Mycroft’s and Colin’s, lines of work – something both richly confectionery and tantalizingly historical, and something that poses a possible solution to Mycroft’s upcoming quarterly quandary.

At the juncture of the two mountain chains that bisect Switzerland north-to-south and east-to-west, there lies a strategic pass: and guarding the heart of that pass is a garrison town called Andermatt. The place is placid in the obvious way that only army towns with a secret to keep can be. On the surface everything seems quite calm, the normal Swiss efficiency overlaying everyday life and the normal tourist influx to the local ski areas, while Swiss soldiers on deployment come and go, mostly by rail, doing yearly duty rotations and coming back from operational maneuvers in the most S.O.P.-ish manner.

Mycroft, of course, by virtue of his office knows for a certainty what some Swiss suspect – that all the mountains around Andermatt are tunneled deep with caves not made by nature, and stuffed full nigh to bursting with assorted military hardware of a nature that would cause the most dreadful fuss if word ever got out. Of course it does not: here also the Swiss are most efficient. What Mycroft knows about the business often makes him smile… but not as much as he now smiles about the Andermatt neighborhood’s great nonmilitary secret. For just over the mountain wall to the eastward, through the smaller gateway valley called the Oberalppass, lies something far more interesting to Mycroft in the near term than the three mountains with the fighter-plane dispensers inside, the concealed death rays, and the buried nukes. And this secret is… a cake.

It must be said here that if Mycroft has another weakness besides cake, it’s an unquenchable thirst for life’s resonances. If one can see Moriarty as a manipulative, string-pulling, malice-bloated spider at the heart of a farflung web of information meant to be turned to evil purpose, then one can also conceive of Mycroft as the queen bee (yes, shut up, Sherlock, truly it’s getting quite old) at the heart of a vast, humming hive of historical and modern data; an exquisitely tone-sensitive analyst tuned to the chorused thrumming of past, present and likely future, and graced with the synthesis gift, the ability to hook that old or distant or unlikely solution to this new problem and cause things to sort themselves out for the best. Very occasionally, being human, he fails at this – especially and most painfully when dealing with problems closest to him. The resonances tend to fall out of phase then, or their sines cancel – and when he fails, he does so, to his endless grief, spectacularly. But mostly Mycroft succeeds, and as a result goes on year by year professionally listening to the hum of history, trying to stay alert to past errors while analyzing what’s in tune, what’s not, and how it all resonates with the now. And the resonances are always key. They’re a sign of the universe trying to heal its own wounds or suggesting ways to put its own problems right, and Mycroft has learned that he ignores them at his peril.

When Colin started describing to Mycroft what lay up past the Oberalp mountain wall, this particular resonance thrummed right down into Mycroft’s bones, and his mouth started watering as he heard not only what went into the cake, but who was making it. Not too far over the Oberalppass from Andermatt, Colin told him, on the main pass road, is a little town called Sedrun. It is a quiet place, at once (in the classic Swiss manner) gracious to visitors and inturned and suspicious of strangers in the way of small country towns everywhere. But this place holds something unusual hidden at its heart. In Sedrun’s confiserie works a direct descendant of one of the great names among the professional confectioners whom the Swiss of centuries past called “sugar-bakers”. These men (and a very few women) moved among the great courts of Europe at the beck and call of royalty – free agents who shifted at will from ducal to royal to imperial court for vast sums of money or other considerations – and everywhere they went, they baked pastries and cakes of fabulous quality, and constructed monumental confections beyond the skill of mere mortals.

But these superstar chefs of their time came to carry with them more secrets than just how to make perfect millefiori-style sugar plate that looked like Venetian glass, or what mixture of flours in the dough would produce the optimum rise and flakiness in that (then) hot new treat, the croissant. Wearers of the perfect cover story, and free to travel where lesser men could not because of the skills in their hands and the recipes in their heads, the sugar-bakers pioneered professional organized espionage – spying for one petty king or count or grand duke against another, turning double or triple agent as it pleased them, courting reward and risking death for fun or the joy of travel or the pleasure of matching wits with their rivals (or their clueless masters) and coming off best. They were the great-great-grandparents of the agents of MI5 and MI6, playing the Great Game in times and circumstances as deadly as our modern ones… but their preferred weapons were flour sieves and pastry bags. Their stories are hardly ever told in our time. But again and again the sugar-bakers quietly changed the course of history and the face of political Europe, while at the same time spending their days interleaving butter a hundred layers deep with dough and marzipan, or perfecting the stable buttercream filling.

The cake of Sedrun – a multilayer chocolate torte with an unusual array of icings – was based on a family recipe a quarter-millennium old, and was being baked by the direct descendant of one of these lost experts. Mycroft could no more have refused the prospect of tasting a cake of such noble lineage than he could have refused to shake the umbrella off his closest-kept secret and match swords with his brother under the summer trees of their childhood, were Sherlock only to pick up a blade and challenge him one more time.

So having heard the tale, Mycroft bided his time until an excuse arose to take him to Zürich (a tête-a-tête with an unfortunate British-affiliated private banker caught deep in most ill-advised weapons-related money laundering). Then, that distasteful business handled, in company with Anthea he made his way a couple hours’ drive south and east in the big embassy-lent car, down EuroRoute 2 to the Gotthard Pass, through the camo-ridden streets of Andermatt, and finally up over the Oberalppass to Sedrun. There, on the north side of the two-lane main road, he found the confiserie of his desire. It was no more than the bottom floor of a brown three-story chalet with awninged cafe tables outside and a wood-paneled coffee shop attached: a simple tidy quarry-tiled space full of a truly divine scent of baking bread and a number of polished pine tables and chairs, the whole of it no bigger than Speedy’s. Mycroft sat down at a table for two and ordered a slice of the cake.

When it arrived on the shining table on its plain white plate, Mycroft’s casually ironic thought about the need to seek out a Moriarty among cakes rose up for reconsideration and took him by the throat. The cake’s surface was pale, slick and glossy, elegant and smooth – but underneath, it was dark, dark at heart. Mycroft had rarely gotten the sense before that while he was sizing up a piece of cake, it might be doing the same to him. He was getting it now.

He picked up his fork post haste, stuck it deep into the thing before it could start coming up with any clever ideas, and abandoned himself wholeheartedly to pleasure.

Normally, as a general indicator of a cake’s quality, Mycroft timed himself to see how long it took to finish a slice. This time… he forgot. It wasn’t that time exactly stood still while he was eating, but it certainly slowed down to an amble and paused occasionally to admire the scenery.

Afterwards Mycroft stood up very quietly, ordered himself a milchkaffee, and strolled out briefly through the scatter of sidewalk tables, past gossiping town housewives and middle-school kids chattering in Romansch, past where Anthea sat texting busily away with a glass of the local soft Fendant white wine in front of her. There he stood on the sidewalk and looked westward up the curving pass road, while considering his options and doing sums in his head.

There the afternoon sun had already slid out of sight downsky in a wash of misty air, blinding beams from it striking upward from behind the towering jagged snow-dappled peaks of Oberalp and Piz Cavradi, silhouetting them: rays of a crown of white fire against the paling blue. Mycroft stood there for a little, breathing in that very clean, already-cooling air, thinking of old mistakes made, the pain of making them, the price of putting them right, and the need to keep oneself on an even keel while doing so – because sometimes mere bare self-denial serves nobody’s best interests. Behind him, up the grassy hill behind the bakery, cowbells were making a quiet musical tunk, tunk sound. Across the road, out of sight on the downslope but very close, icy glacier-fed water rushed and tumbled over a bed of big rounded stones; for this was the southernmost source of the Rhine, and the soft kicked-up spray of the living water hung the scent of new beginnings on the still air.

Mycroft stood there a few seconds more, then went back in for his coffee. He sat and drank it, musing; then went to the bakery counter to pay his bill, and finally asked to speak to the master baker.

The man wasn’t long coming out – a craggy silver-haired man of middle height whose stance and look immediately put Mycroft in mind of someone at home. Post-military, Mycroft immediately perceived: but considering the combination of Swiss military tradition (all adult males serve in some capacity) and this particular neighborhood, that was obviously going to be the rule rather than the exception. High-ranking, but gave it up to carry on the family tradition when his father died. Happily married, training his son to carry on the tradition after him, but not ready to retire just yet: tempers his chocolate personally. Proud: and in command. …A few minutes’ conversation made it plain that under no circumstance would this gentleman ever part with the recipe: and of course that made sense. Had to try, though. Nothing ventured, nothing gained…. But after a few minutes more, the two of them worked out an arrangement by which someone from the British Embassy in Bern who had business down this way would swing by once every couple of months, pick up a cake, and send it home to London in the daily diplomatic pouch.

And so it would come to pass. The challenge would be to make such a cake last him two months: if it went away before then (not, of course, counting pieces given to other people) Mycroft would hone his resolve to a finer edge and try again. If he succeeded, then he would chalk up a small victory and allow himself another cake. As he went out to the car (where Anthea was already ensconced) carrying the string-tied cake box, the matter was already managed and ready to be dismissed. In his own mental management storage – no palace of the mind, but a utilitarian space that looked far more like the warehousing facility in Raiders of the Lost Ark – the cake was already sliced up and tucked away in a virtual twin of his own larder freezer.

But the satisfaction of what he’d acquired remained, and Mycroft smiled slightly to himself as he got into the car, already planning the disposition of those careful slices. A few seconds later the driver pulled out, making a doubtless-illegal U-turn in the middle of the Oberalppass road and heading west again for the tall stack of switchback curves that would lead back down to Andermatt and the northbound motorway.

Then Mycroft sighed: because enjoyable as such indulgences were, they were better far when shared. However, Anthea would unfortunately refuse such an offering, as her preferences did not run to chocolate. Sherlock, as a message to the present’s source, would bin it without a second thought. John would most likely eat it, out of a desire not to waste, if nothing else: but his acceptance of the gesture would likely cause him complications later, and Mycroft had no desire whatsoever to destabilize that particular household dynamic. Mrs. Hudson, however, would enjoy some. Mycroft tagged one of those in-mind slices with her name. And Colin must of course have a slice. A moment later that one had been moved into the kitchen freezer in Mycroft’s virtual version of the Diogenes Club.

And there was – he thought while the car wound its way down the switchbacks – one more possibility.

Mycroft hesitated. Yet, still…

Nothing ventured, nothing gained.

He pulled his phone out. Anthea glanced over at him. “Something you need, sir?”

Mycroft shook his head. He dialed: waited for the connection: and smiled a small secret smile.

“DI Lestrade, please. …Yes, thank you, I’ll hold…”

*See also Dark Kingdom: The Dragon King (the name under which it aired on SyFy in 2004) and Sword of Xanten (the name under which it aired on Channel 4 in the UK). It aired in most major world markets through one or another of its co-production partnerships, and as a result it had more titles than you could shake a dessert fork at.